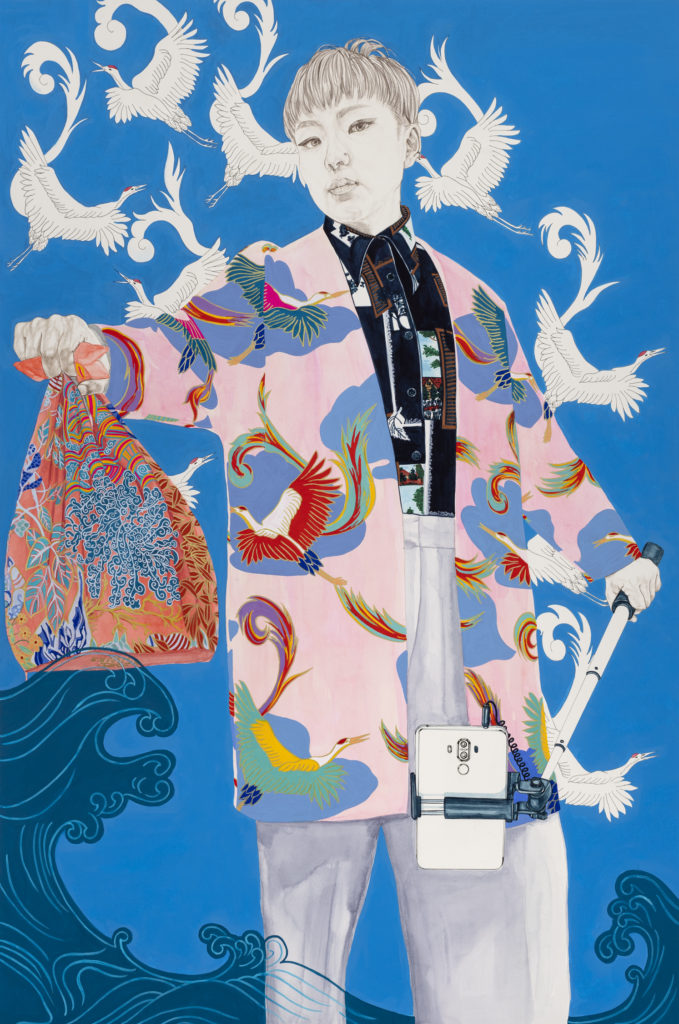

Kira Nam Greene is a New York-based painter. Greene’s paintings explore feminism, materialism and beauty. Her recent series and NFT Women in Possession of Good Fortune was featured as part of the EVERY WOMAN BIENNIAL 2021 at Superchief Gallery in New York City.

You came to painting in a really interesting way, I would love to hear a bit about your artistic background, specifically where and how you grew up and how you feel that shaped you as an artist?

I grew up in Korea in an environment where everyone was very academically oriented with very typical Asian parents. I was expected to become a doctor, a lawyer or a professor but I was already interested in literature and art growing up. I actually studied political science specializing in political economy and then came to the United States to get my Ph.D. Everybody had really high expectations and I was in a field that was dominated by males in Korea. So the expectations were that I would come back and do very meaningful things there. But, somehow, being in America changed my view and after living here for a while I decided I didn’t want to go back to Korea. My background was very academic. I think my approach to art has also been affected by that. I read and I think a lot and that’s kind of my natural inclination to try to combine that natural instinct I have with research, focus, labour and more spontaneous expressions as well.

How would you describe your creative process?

I am really connected to materials because I had this very long period of immersion in art. So I would go out of my way to find out more about a new medium that I was interested in by either asking people, watching videos or reading books. The materiality of each medium is very important to me and I have two tracks in terms of material exploration that I’m interested in. One is works on canvas or panels that involve oil painting. But I’m really interested in what other materials I can bring in to make the surface as variable and diverse as possible. I use a lot of acrylic paint, acrylic wash, and mixed media material. Even within oil painting, I use different techniques. I’m invested in realism and I use very traditional mastery techniques with glazing and underpainting. The other track is working on paper. I’m interested in watercolour and coloured pencils, particularly from a feminist point of view because those are the materials that were relegated as “women’s materials.” Of course, it has changed over the years but because of that, I try to use these materials on paper to highlight the inherent beauty of those mediums. Trying to make these works on paper the same scale as the works on canvas so that it’s not a drawing but a painting. Going against the inherent bias that watercolour or colour pencils are more of a “crafty women’s material,” and in hopes to erase that history in a more profound way.

What was the genesis of your series Women in Possession of Good Fortune?

The original genesis of this work happened in 2017, after the women’s March and Trump’s election. Like everyone in New York, I was disparaged essentially. I went to the Women’s March as a last resort of ‘what can we do?’ And then I came out of it with a resolve to connect with other women and a venue to meet in collective action. I started thinking more deeply about the power of women and how women are portrayed in society. So I decided to make portraits of the women in my life who are powerful, who are creative and who are in possession of their good fortune. And along the way, when I was trying to figure out how to portray these women as powerful as possible, I drew on art history, specifically the connection to Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors. This portrait of two French ambassadors that Holbein painted in England. There are many portraits of male intellectuals and high-ranking officials of the time where they were shown with symbols and allegories of their professional successes where you would see the scientific instruments and books. Whereas, paintings of women were traditionally done as portraits depicting marriage and presented as trading cards just to show the beauty of the women and to show that they were marriageable. So, I tried to kind of flip that coin and show women in a position of professional success, surrounded by their personal history and put symbols and allegories of their professional successes. All the elements of these paintings are very personally related to who they are as professionals, as human beings, as mothers… Both their professional history and personal history are woven into the painting.

This is where my research comes in because I tried to figure out how to translate their personal history into visual allegories or metaphors or symbols, and I did that research for each painting. The title of the series itself comes from Jane Austen’s novel, Pride and Prejudice, where the first line of the book is “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” Jane Austin was a total feminist in thinking about the situations of women in the 17th and 18th centuries, England. I thought about the men in a position of good fortune, meaning rich men that women have to marry and what that meant to be able to maintain a societal and a professional position. I wanted to flip that on its head and designate that these are women in a position of good fortune and their fortune is not only in their professional successes but also a position of power, possession of personality, and of polish.

Do you consider yourself and your work a form of activism?

As a Korean American woman and immigrant, my perspective has always been in the interest of inclusion and diverse representation of power. So defining the term powerful in a different way, because there’s another feminist point of view of power that needs to be expanded, not only residing in the economy and political power but unless you expand that power in other areas, society won’t change as much as we want it to change. So this is one of my endeavours in terms of portraying such a diverse group of women, but it’s also not just women, the piece that was minted for the Every Women Biennial, the subject that was portrayed, they are a gender-fluid person, not a woman, so their pronouns are they/them. I think age is also really important. A lot of painters tend to paint people in their age groups. I wanted to paint a really diverse age group and say that these are all my friends, these are all the people that I care about. I like to think of myself as a cultural worker rather than an activist. I am a person who works to move the culture in a different way than where it is. So in that sense, it includes activism, but I’m not like a vanguard of social activism where I go out on the street and protest and organize events. I participate in marches and organizations when I can, but I’m most invested in ideas and changing culture, which is through my art and trying to move conversations in a way that can make people more aware of what’s going on and expand the conversation.

I’m curious how you feel about bringing your physical paintings onto an NFT platform, and what your experience has been so far?

This is kind of a dilemma, a curiosity, and I don’t know what to think of it. This is something very new, so I am curious about the possibility of more democratic distribution of images and the idea of NFTs and cryptocurrency in a utopian interpretation that there is no middle man, you engage directly with your audience and there’s no institutional involvement. This utopian idea is probably not the reality, but the possibility is there. I don’t know where it’s going but I’m curious who might respond to my NFTs versus my physical paintings and how my paintings translate to a digital image.

Kira Nam Greene

Website: kiranamgreene.com

Instagram: @kiranamgreene